Spotted Owl

In the ancient, mist-shrouded forests of the Pacific Northwest, where towering cedars and Douglas firs weave a cathedral of green and the air hums with the pulse of untouched wilderness, the Spotted Owl reigns as a reclusive guardian of the old-growth realm. Known scientifically as Strix occidentalis, this elusive raptor embodies the quiet majesty of ecosystems teetering on the edge, its haunting calls echoing through the night like whispers from a fading world. Native to western North America—from British Columbia’s coastal rainforests to California’s Sierra Nevada, with isolated populations in Arizona and Mexico—the Spotted Owl has become a symbol of conservation battles, its survival intertwined with the fate of the primeval forests it calls home. With a story steeped in both ecological wonder and human conflict, this owl captivates as a testament to nature’s intricate balance.

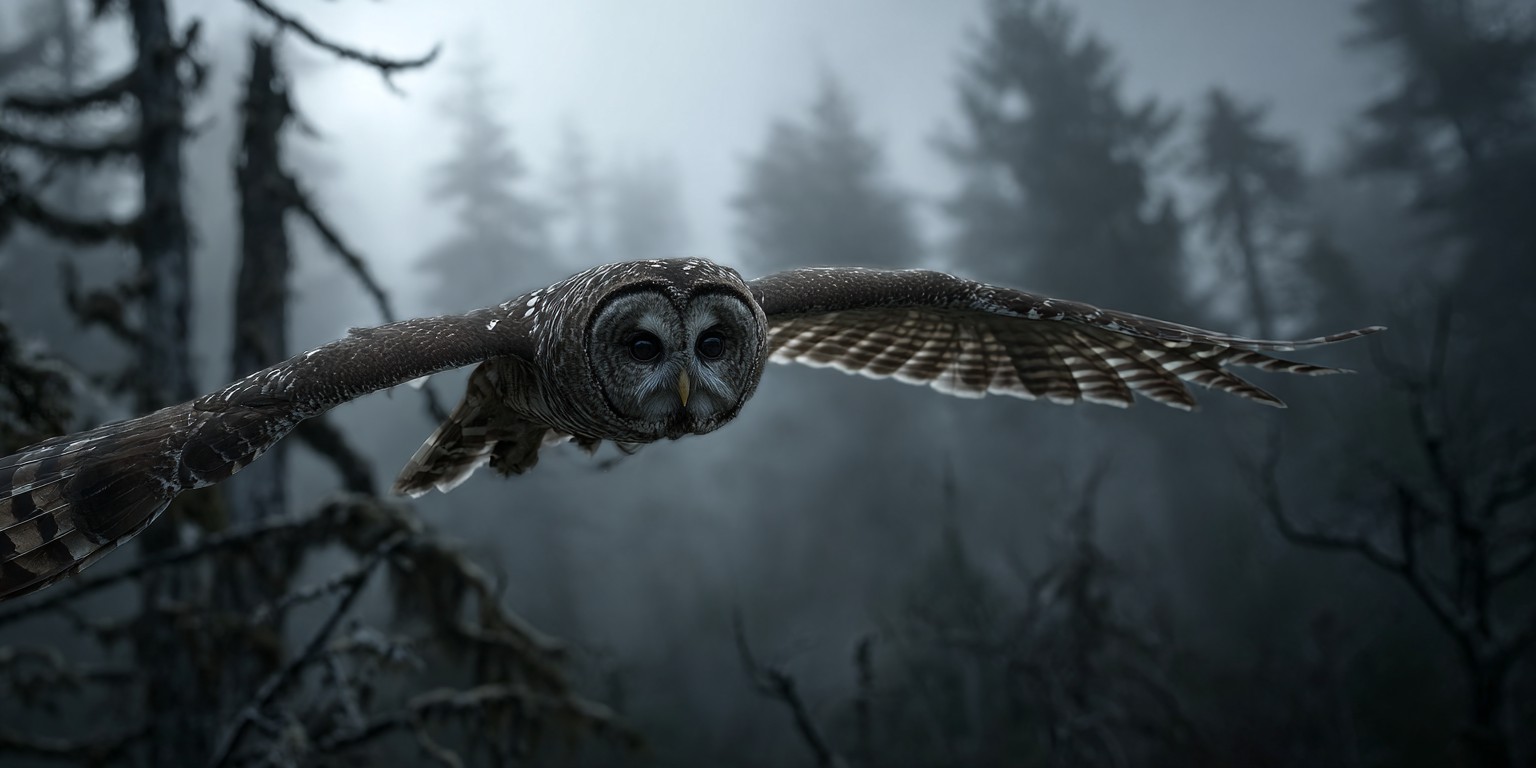

Physically, the Spotted Owl is a medium-sized marvel, blending subtlety with strength. Measuring 16 to 19 inches in length, with a wingspan of 3.5 to 4 feet and a weight of 1 to 2 pounds, females are slightly larger than males, their robust frames suited for nesting duties. Its plumage is a tapestry of camouflage: rich chocolate-brown upperparts speckled with white spots—like stars scattered across a twilight sky—merge with creamy underparts barred and mottled for seamless blending into tree bark. The facial disc, broad and rounded, is a soft gray-brown framed by concentric rings, accentuating large, dark eyes that gleam with nocturnal intensity, optimized for low-light hunting. Unlike its Great Grey cousin, it lacks ear tufts, its smooth head enhancing acoustic precision through asymmetrical ears that pinpoint prey rustles. Its talons, sharp and curved, grip with lethal force, while flight feathers edged with soft serrations ensure silent glides through dense canopies, a ghostly hunter in the forest’s embrace.

Habitat defines the Spotted Owl’s existence, anchoring it to old-growth coniferous forests—ancient stands of redwood, hemlock, and pine over 200 years old, where multi-layered canopies, dead snags, and fallen logs create a labyrinthine haven. Its core range spans the Pacific Northwest, from southwest Canada through Washington, Oregon, and northern California, with the Northern Spotted Owl (S. o. caurina) dominating these wetter climes, while the California Spotted Owl (S. o. occidentalis) inhabits drier Sierra forests, and the Mexican Spotted Owl (S. o. lucida) clings to canyonlands farther south. These owls are sedentary, rarely straying from territories of 2 to 5 square miles, shunning open landscapes or young forests for the complexity of mature woods. Breeding unfolds in late winter to early spring, February to May, with monogamous pairs—often lifelong—exchanging soft, four-note “hoot-hoot-hoo-hoot” calls that resonate like a forest lullaby. Nests are cavities in broken tree tops, old woodpecker holes, or platforms left by hawks, lined sparingly with feathers. Females lay one to three white eggs, incubating for about 30 days while males hunt, with chicks fledging after 5 weeks, their fluffy forms trailing parents for months to learn the art of survival in a shadowed world.

Behaviorally, the Spotted Owl is a nocturnal recluse, its life a study in discretion and precision. By day, it roosts high in dense foliage, nearly invisible against trunks, stirring only at dusk to preen and stretch, its flexible neck swiveling 270 degrees to scan for threats. Territorial to a fault, pairs defend their domains with vocal duets or aggressive dives against intruders like Great Horned Owls, their larger predators. Social bonds are subtle yet strong, with mates sharing quiet contact calls—whistles and barks—or mutual grooming to reinforce ties. Intelligence glimmers in their adaptability; they’ve been observed caching prey in mossy crevices or adjusting hunting patterns to seasonal shifts. Their vocal repertoire, a mix of hoots, screeches, and soft coos, serves as territorial markers or courtship songs, with some calls mimicking other species to deter rivals. Daily routines center on energy conservation—perching for hours, bathing in forest streams, or sunning briefly to warm feathers—ensuring survival in chilly, damp habitats.

Hunting showcases the Spotted Owl’s mastery of stealth, a silent assassin tailored to dense forests. Specializing in small mammals—flying squirrels, woodrats, voles—it perches patiently on low branches, then glides in shallow arcs to snatch prey with talons that crush spines instantly. Unlike broader omnivores, its diet is narrow, with 70 percent tied to arboreal rodents, though birds, insects, and bats supplement in lean times. In one remarkable adaptation, Northern Spotted Owls track the nocturnal glides of flying squirrels, striking mid-air with acrobatic precision. Hearing reigns supreme, with ears detecting rustles through thick undergrowth, while vision—tuned to twilight—spots subtle movements. Pellets, regurgitated daily as compact wads of fur and bones, pile beneath roosts, offering scientists dietary insights that map forest food webs, critical for monitoring ecosystem health as prey populations fluctuate with logging or climate shifts.

In falconry and wildlife centers, the Spotted Owl is a rare guest, its protected status and specialized needs limiting its role to conservation education rather than hunting displays. In sanctuaries like California’s Sierra Nevada Raptor Center or Oregon’s Cascades Raptor Center, rehabilitated or imprinted owls appear in controlled settings, gliding to gloved hands to illustrate their forest-bound lives. Training is delicate, using food rewards like mice to build trust, with minimal hood use to preserve natural behaviors, as their shy nature demands gentle handling. These centers weave narratives of ecological struggle, from Native American reverence for owls as forest spirits to modern battles against deforestation, highlighting the Spotted Owl’s role as a flagship species for old-growth preservation. Captive lifespans reach 20-25 years, outpacing wild averages of 10-15 due to predation and habitat risks, making them enduring ambassadors for their vanishing homes.

The Spotted Owl’s saga is one of peril and advocacy, a poster child for environmental conflict since the 1980s when logging in the Pacific Northwest threatened its survival. Listed as threatened under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (Northern subspecies since 1990, Mexican since 1993), and vulnerable in Canada, populations have plummeted—Northern Spotted Owls number fewer than 3,000 pairs, with declines of 50-75 percent since the 1980s due to clear-cutting that razed 70 percent of old-growth forests. Competition from invasive Barred Owls, which outcompete and hybridize with Spotted Owls, exacerbates losses, as do climate-driven wildfires and drought that disrupt prey. Conservation efforts fight back: the Northwest Forest Plan of 1994 protects millions of acres, creating reserves where logging is restricted, while experimental Barred Owl culls test coexistence strategies. Nest boxes and hacking programs bolster breeding, and satellite tracking maps territories, revealing how owls adapt to fragmented landscapes. Community engagement, via live cams and citizen science, rallies public support, though tensions with timber industries persist, framing the owl as a lightning rod for economic versus ecological debates.

Anecdotes from the Spotted Owl’s world shimmer with quiet wonder. In Oregon’s Deschutes National Forest, one owl was filmed “mantling” over a woodrat, wings spread like a cloak to hide its prize from ravens, while in California, pairs have nested in fire-hollowed snags, turning scars into sanctuaries. Researchers recount owls tracking fieldworkers, curiously shadowing from above, or responding to recorded calls with eerie accuracy, as if joining a forest chorus. In captivity, they display quirks—tilting heads at reflections or “churring” softly at familiar voices—hinting at a reserved intelligence. Their pellets, unpacked in labs, reveal ecosystems in flux, from squirrel bones signaling stable forests to insect fragments warning of pesticide impacts.

As we reflect on the Spotted Owl, it stands as a shadowed sentinel of ancient woods, its spotted form a reminder that fragility and strength coexist in nature’s heart, urging us to preserve the forests where its calls still linger. In wildlife centers, where its silent glides captivate, this owl beckons us to listen to the wild’s fading song—one stealthy hunt, one haunting hoot at a time—ensuring its legacy endures in the green cathedrals it calls home.